library(blackmarbler)Case study: Nighttime lights

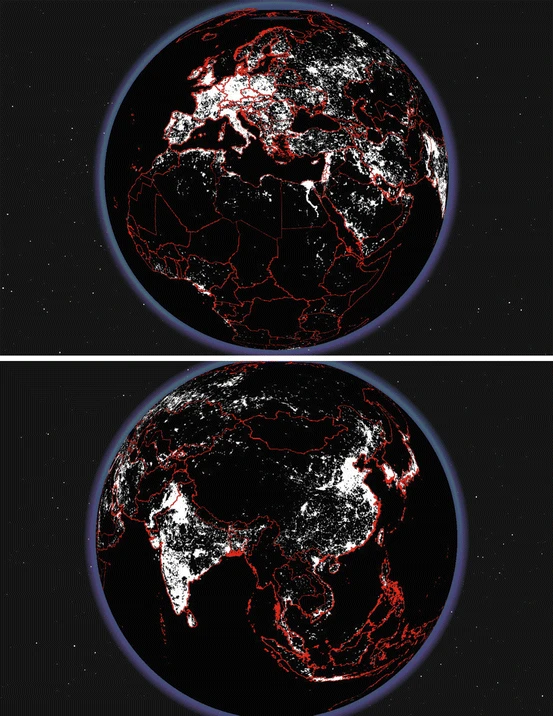

NASA’s Blackmarble 🌑

NASA’s Blackmarble uses VIIRS DNB sensors on board of the Suomi NPP and NOAA-20 satellites. The VIIRS DNB has a high spatial resolution of 500 m and is calibrated and corrected for atmospheric, terrain, lunar BRDF, thermal, and stray light effects. This is resulting in faster retrieval time and less noise, facilitating research based on daily, seasonal and annual changes in NLs (Levin, 2020). Therefore, NASA’s Blackmarble is the most commonly used NL data set in recent studies.

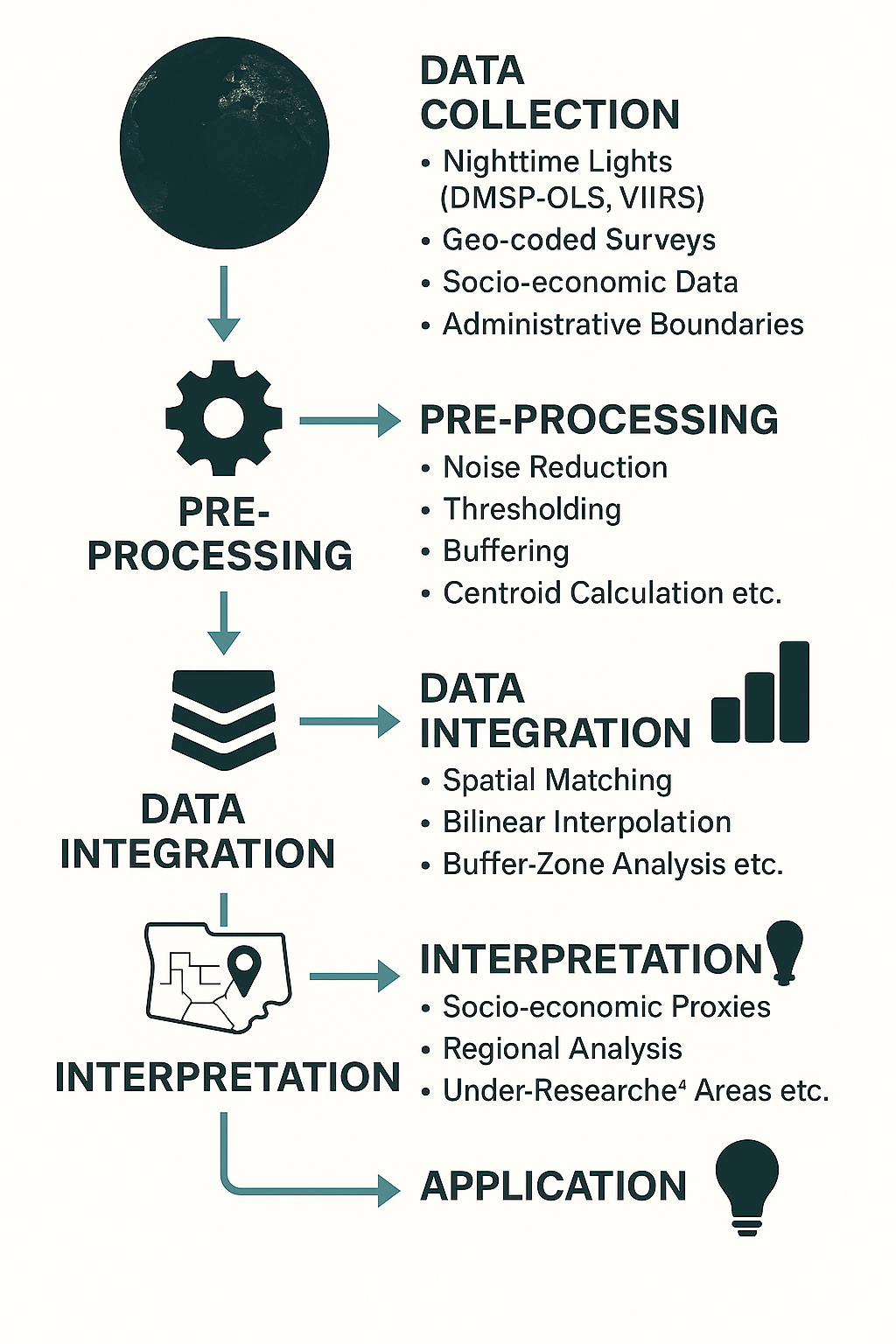

Introduction case study

Working with NL data can give insights to natural and human activity, as well as complex socioeconomic phenomenons. In this case study we will focus on the relation between NL and population in Los Angeles County. We will try to visualize correlations and test the accuracy of NL as indicator for socio demographic statistics. The workflow we will follow looks like this: data retrieval using an API, pre-processing (log-transformation), sub-setting (masking & cropping) the AOI, disaggregation (matching resolution), stacking layers, data preparation & model training (randomForest, imputation logics), descriptive statistics.

In case you are not all up to date in working with raster layers and data cubes, please have a look at that topic again.

R package blackmarbler

blackmarbleR by Robert Marty and Gabriel Stefanini Vicente (2025) supports easy access to NASA’s Black Marble API. Let’s check out their vignette to set up an account and the data retrieval.

Data retrieval

The function bm_raster() to retrieve the nighttime lights requires as input an sfobject to determine the spatial extent of the downloaded data. The object must be in WGS84.

We will focus on California. Let’s load US states shapefiles with the tigris package and subset to California.

CA_sf <- tigris::states(progress_bar = FALSE) |>

dplyr::filter(STUSPS == "CA") |>

sf::st_transform(crs = "EPSG:4326")Retrieving data for the year 2024print(CA_sf)Simple feature collection with 1 feature and 15 fields

Geometry type: MULTIPOLYGON

Dimension: XY

Bounding box: xmin: -124.482 ymin: 32.52951 xmax: -114.1312 ymax: 42.0095

Geodetic CRS: WGS 84

REGION DIVISION STATEFP STATENS GEOID GEOIDFQ STUSPS NAME LSAD

1 4 9 06 01779778 06 0400000US06 CA California 00

MTFCC FUNCSTAT ALAND AWATER INTPTLAT INTPTLON

1 G4000 A 403673433805 20291632828 +37.1551773 -119.5434183

geometry

1 MULTIPOLYGON (((-119.9999 4...plot(sf::st_geometry(CA_sf))

Once you have set up your profile at NASA’s Earth Data Portal and generated your API token, you can assign it to an object in R for the data retrieval.

bearer <- Sys.getenv("NASA-token")

# If you work locally, directly assign it

# bearer <- "YOUR_TOKEN"Now we can download the data from NASA’s API.

CA_nl_stack <- bm_raster(

roi_sf = CA_sf,

product_id = "VNP46A4", # for yearly data

date = 2017:2020, # same four years like our population data

bearer = bearer, # your API token

output_location_type = "file", # we want to store geotiff on disk

file_dir = "./data/", # where to store geotiff

file_return_null = FALSE # also create SpatRaster file

)How to store as GeoTIFFs

By default, the function writes the data to theR environment (output_location_type = "memory"). If you want to store it as single GeoTIFFs, specify output_location_type = "file and the file path with file_dir=. file_return_null= further specifies whether the data is additionally loaded to the R environment.

Let’s have a quick lock at our data:

CA_nl_2020 <- terra::rast("./data/VNP46A4_NearNadir_Composite_Snow_Free_qflag_t2020.tif")

print(CA_nl_2020)class : SpatRaster

size : 2275, 2485, 1 (nrow, ncol, nlyr)

resolution : 0.004166667, 0.004166667 (x, y)

extent : -124.4833, -114.1292, 32.52917, 42.00833 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

coord. ref. : lon/lat WGS 84 (EPSG:4326)

source : VNP46A4_NearNadir_Composite_Snow_Free_qflag_t2020.tif

name : t2020

min value : 0.0

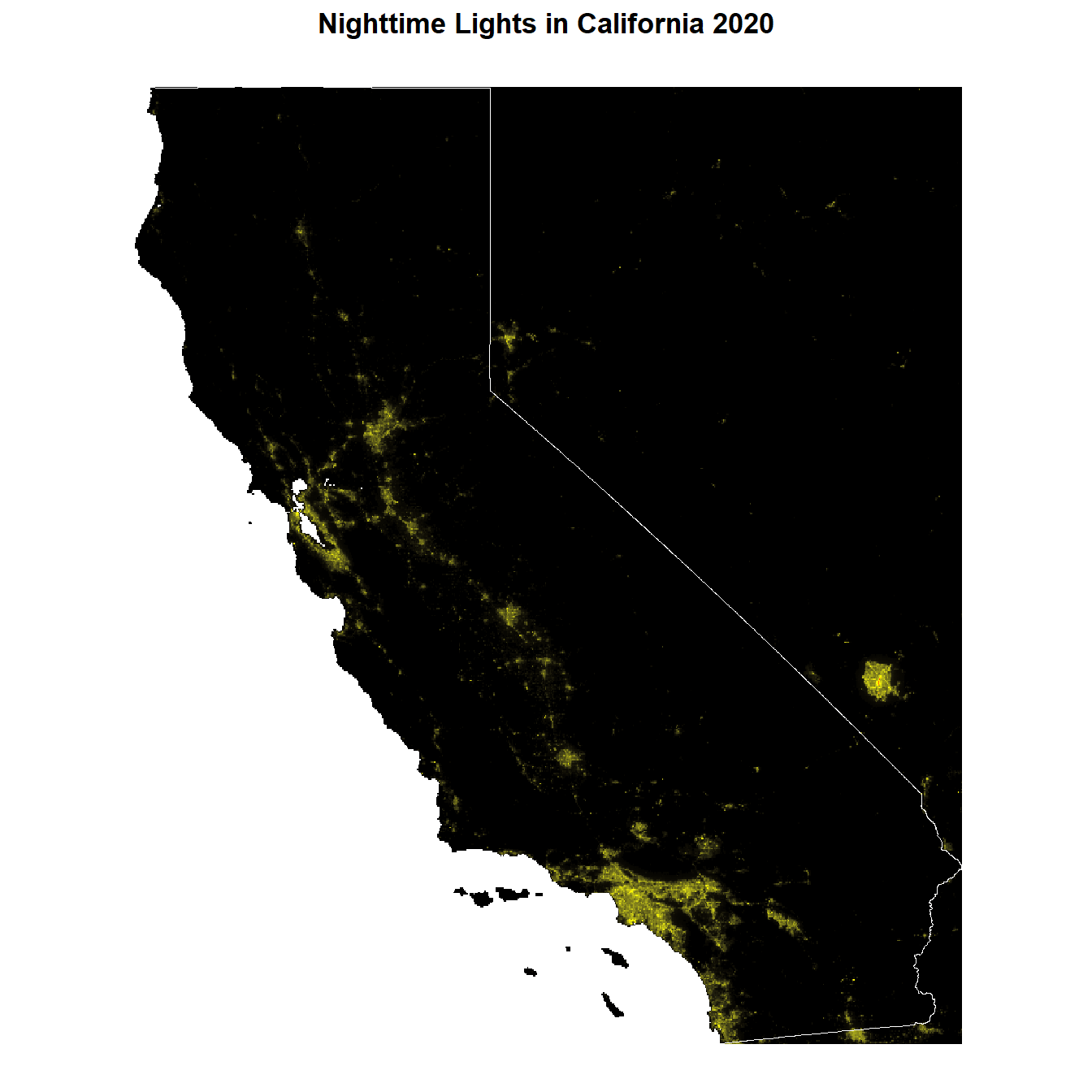

max value : 269.2 Pre-processing

The data is right-skewed. We perform a log-transformation to account for that. Let’s have a look at our data now.

CA_nl_2020[] <- log(CA_nl_2020[] + 1)

ggplot() +

geom_spatraster(data = CA_nl_2020) +

geom_sf(

data = CA_sf,

fill = "transparent",

color = "white",

size = 4

) +

scale_fill_gradient2(

low = "black",

mid = "yellow",

high = "red",

midpoint = 3,

na.value = "transparent"

) +

labs(title = "Nighttime Lights in California 2020") +

coord_sf() +

theme_void() +

theme(

plot.title = element_text(face = "bold", hjust = 0.5),

legend.position = "none"

)<SpatRaster> resampled to 500980 cells.

Sub-setting

In order to define our AOI to Los Angeles County 🌃 we first need to:

# Load LA County file

LA_county <- tigris::counties("CA",

progress_bar = FALSE

) |>

filter(NAME == "Los Angeles") |>

st_transform(crs = "EPSG:4326")Retrieving data for the year 2024# Subset to "mainland" California and

# exclude the two islands Santa Catalina and San Clemente

LA_county <- LA_county %>%

st_cast("POLYGON") %>%

mutate(area = st_area(.)) %>%

slice_max(area, n = 1)Warning in st_cast.sf(., "POLYGON"): repeating attributes for all

sub-geometries for which they may not be constantprint(LA_county)Simple feature collection with 1 feature and 19 fields

Geometry type: POLYGON

Dimension: XY

Bounding box: xmin: -118.9517 ymin: 33.65955 xmax: -117.6464 ymax: 34.8233

Geodetic CRS: WGS 84

STATEFP COUNTYFP COUNTYNS GEOID GEOIDFQ NAME

1.2 06 037 00277283 06037 0500000US06037 Los Angeles

NAMELSAD LSAD CLASSFP MTFCC CSAFP CBSAFP METDIVFP FUNCSTAT

1.2 Los Angeles County 06 H1 G4020 348 31080 31084 A

ALAND AWATER INTPTLAT INTPTLON area

1.2 10516008433 1784982940 +34.1963983 -118.2618616 10863687022 [m^2]

geometry

1.2 POLYGON ((-118.0288 33.8733...plot(st_geometry(LA_county))

Now that we have an sf file of our AOI, we can prepare our two raster files.

# Create LA raster files for population and night lights in 2020

LA_pop_2020 <- terra::rast("./data/US-CA_ppp_2020_1km.tif") |>

terra::mask(terra::vect(LA_county)) |>

terra::crop(LA_county)

LA_pop_2020[] <- log(LA_pop_2020[] + 1)

LA_nl_2020 <- terra::mask(

CA_nl_2020,

terra::vect(LA_county)

) |>

terra::crop(LA_county)Disaggregation

Our two raster files have the same CRS and (almost same) spatial extent. Unfortunately, the resolution (cell size) differs. Our population data is on an approx. 1km grid and our night lights data on an approx. 500m grid.

Checking cell size

print(LA_pop_2020)class : SpatRaster

size : 140, 157, 1 (nrow, ncol, nlyr)

resolution : 0.008333333, 0.008333333 (x, y)

extent : -118.9512, -117.6429, 33.65792, 34.82458 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

coord. ref. : lon/lat WGS 84 (EPSG:4326)

source(s) : memory

varname : US-CA_ppp_2020_1km

name : US-CA_ppp_2020_1km

min value : 0.000000

max value : 9.843707 print(LA_nl_2020)class : SpatRaster

size : 280, 313, 1 (nrow, ncol, nlyr)

resolution : 0.004166667, 0.004166667 (x, y)

extent : -118.95, -117.6458, 33.65833, 34.825 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

coord. ref. : lon/lat WGS 84 (EPSG:4326)

source(s) : memory

varname : VNP46A4_NearNadir_Composite_Snow_Free_qflag_t2020

name : t2020

min value : 0.000000

max value : 4.400603 So how can we align two layers? There are multiple ways, like always in R. Firstly we will try out terra::disagg() / terra::aggregate() . By splitting each cell into smaller parts we can increase the resolution of a grid to adjust it to another. It is the simplest and fastest way to harmonize multiple cell sizes and increase their resolution without altering original values.

First option: Increase resolution for population data

# Increase resolution for population data

LA_pop_2020_high <- terra::disagg(LA_pop_2020,

fact = c(2, 2),

method = "bilinear"

)

# There is still a slight mismatch due to rounding errors (one more ncol)

# Let's crop to the spatial extent of the nightlights data

LA_pop_2020_high <- crop(

LA_pop_2020_high,

terra::ext(LA_nl_2020)

)# Cross-check

res(LA_pop_2020_high)[1] 0.004166667 0.004166667res(LA_nl_2020)[1] 0.004166667 0.004166667ext(LA_pop_2020_high)SpatExtent : -118.9512495092, -117.64708284775, 33.65791673341, 34.82458339541 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)ext(LA_nl_2020)SpatExtent : -118.95, -117.645833333333, 33.6583333333333, 34.825 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)# A small rounding error in extent will prohibit to concatenate

# into a stack. We now force the extent

ext(LA_pop_2020_high) <- ext(LA_nl_2020)Second option: Decrease resolution for nightlights data

# Decrease resolution for nightlights data

LA_nl_2020_low <- terra::aggregate(LA_nl_2020,

fact = c(2, 2),

method = "bilinear"

)

# There is still a slight mismatch due to rounding errors (one more ncol)

# Let's crop to the spatial extent of the population data

LA_nl_2020_low <- crop(

LA_nl_2020_low,

terra::ext(LA_pop_2020)

)# Cross-check

res(LA_pop_2020)[1] 0.008333333 0.008333333res(LA_nl_2020_low)[1] 0.008333333 0.008333333ext(LA_pop_2020)SpatExtent : -118.9512495092, -117.6429161811, 33.65791673341, 34.82458339541 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)ext(LA_nl_2020_low)SpatExtent : -118.95, -117.641666666667, 33.6583333333333, 34.825 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)ext(LA_nl_2020_low) <- ext(LA_pop_2020)Another way to match different grids is terra::resample(). By interpolating the resolution of one layer is adjusted to another one. The advantage: this method accounts more for the real spatial pattern.

# Cross-check

LA_pop_2020_resampled <- resample(

x = LA_pop_2020,

y = LA_nl_2020,

method = "bilinear"

)

res(LA_pop_2020_resampled)[1] 0.004166667 0.004166667res(LA_nl_2020)[1] 0.004166667 0.004166667ext(LA_pop_2020_resampled)SpatExtent : -118.95, -117.645833333333, 33.6583333333333, 34.825 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)ext(LA_nl_2020)SpatExtent : -118.95, -117.645833333333, 33.6583333333333, 34.825 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)Stacking layers

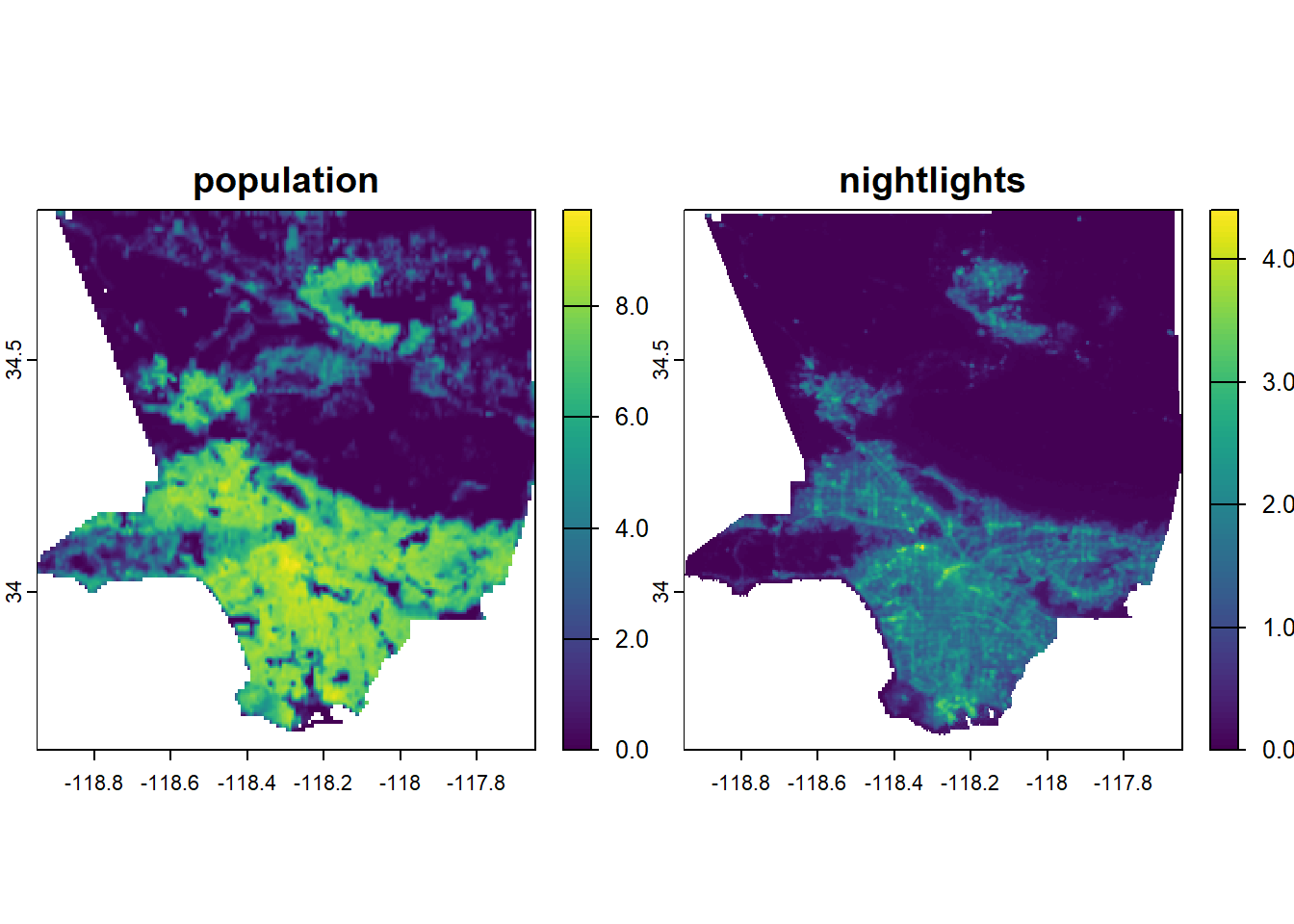

Only when all grids and resolutions of our layers match we can start combining layers into a raster stack.

LA_stack <- c(LA_pop_2020_resampled, LA_nl_2020)

print(LA_stack)class : SpatRaster

size : 280, 313, 2 (nrow, ncol, nlyr)

resolution : 0.004166667, 0.004166667 (x, y)

extent : -118.95, -117.6458, 33.65833, 34.825 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

coord. ref. : lon/lat WGS 84 (EPSG:4326)

source(s) : memory

varnames : VNP46A4_NearNadir_Composite_Snow_Free_qflag_t2020

VNP46A4_NearNadir_Composite_Snow_Free_qflag_t2020

names : US-CA_ppp_2020_1km, t2020

min values : 0.000000, 0.000000

max values : 9.733816, 4.400603 varnames(LA_stack) <- c("population", "nightlights")

names(LA_stack) <- c("population", "nightlights")

terra::plot(LA_stack)

Model Training with Imputation Logics 🏋️♀️

Previous examples follow the idea of interpolating existing data across the spatial domain. Imputation fills in missing values based on a prediction model. Let’s consider our two variables to make up a stylized example:

We know that population density and nightlights is correlated. We could try to predict the missing values for population based on the values of nightlights to generate the higher resolution population data. In order to do that, we train a RandomForest model on the low resolution data of population and nightlights.

library(randomForest)randomForest 4.7-1.2Type rfNews() to see new features/changes/bug fixes.

Attache Paket: 'randomForest'Das folgende Objekt ist maskiert 'package:ggplot2':

margin# Covariates need to be in same size as outcome variable = 1km

LA_nl_2020_resampled <- resample(

x = LA_nl_2020,

y = LA_pop_2020,

method = "bilinear"

)

# Create training data - one row per cell

train_data <- as.data.frame(LA_nl_2020_resampled,

xy = TRUE,

cells = TRUE,

na.rm = FALSE

) |>

left_join(

as.data.frame(LA_pop_2020,

xy = FALSE,

cells = TRUE,

na.rm = FALSE

),

by = "cell"

) |>

rename(

nightlights = t2020,

population = `US-CA_ppp_2020_1km`

)

train_data <- na.omit(train_data)Ready to fit the model and predict population data on 500m grid.

# Fit model

out <- randomForest(

population ~ nightlights,

data = train_data,

ntree = 500

)

# Predict on the 500m grid

# Covariate names need to match

names(LA_stack)[1] "population" "nightlights"pop_500m <- predict(LA_stack, out)

names(pop_500m) <- "population_predicted"

LA_stack <- c(LA_stack, pop_500m)Statistic analysis 🧮

Now we have a million options to analyse our raster stack.

# Global univariate means

global(LA_stack, fun = mean, na.rm = TRUE) mean

population 2.9236307

nightlights 0.5277355

population_predicted 2.7916561# Bivariate correlations

layerCor(LA_stack, fun = "cor", use = "complete.obs")$correlation

population nightlights population_predicted

population 1.0000000 0.8245851 0.8757805

nightlights 0.8245851 1.0000000 0.8731580

population_predicted 0.8757805 0.8731580 1.0000000

$mean

population nightlights population_predicted

population NaN 2.923631 2.9236307

nightlights 0.5277355 NaN 0.5277355

population_predicted 2.7916561 2.791656 NaN

$n

population nightlights population_predicted

population NaN 59392 59392

nightlights 59256 NaN 59256

population_predicted 59256 59256 NaNLiterature

Bruederle A, Hodler R (2018) Nighttime lights as a proxy for human development at the local level. PLOS ONE 13(9): e0202231. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202231

Chen, X. (2016). Using Nighttime Lights Data as a Proxy in Social Scientific Research. In: Howell, F., Porter, J., Matthews, S. (eds) Recapturing Space: New Middle-Range Theory in Spatial Demography. Spatial Demography Book Series, vol 1. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22810-5_15

Dugoua, E., Kennedy, R., & Urpelainen, J. (2018). Satellite data for the social sciences: measuring rural electrification with night-time lights. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 39(9), 2690–2701. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2017.1420936

Freie Universität Berlin. (n.d.). Sensor basics - Remote sensing data [Blog post]. Freie Universität Berlin. Retrieved May 19, 2025, from https://blogs.fu-berlin.de/reseda/sensor-basics/

Levin, N., Kyba, C. C., Zhang, Q., de Miguel, A. S., Román, M. O., Li, X., … & Elvidge, C. D. (2020). Remote sensing of night lights: A review and an outlook for the future. Remote Sensing of Environment, 237, 111443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111443

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. (n.d.). NASA Black Marble. NASA. Retrieved May 14, 2025, from https://blackmarble.gsfc.nasa.gov/

Proville, J., Zavala-Araiza, D., & Wagner, G. (2017). Night-time lights: A global, long term look at links to socio-economic trends. PloS one, 12(3), e0174610. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174610